MANTRA, MUDRA, MANDALA

From the point of view of spirituality the modern era has been devastating. It has tainted our souls to the point that we no longer even know what soul means; it has cut the most powerful instrument of humankind - our science - adrift from conscience, morality and wisdom; it has trivialized economics and politics; it has waged war on mother earth and her children with increasing vengeance and success - fulfilling Francis Bacon's command that we "torture mother earth for her secrets"; it has rendered our youth adrift and without hope or vision; it has bored people in what ought to be the great communal celebration known as worship; it has legitimated human holocausts and genocides from that of the seventy million native people exterminated in the Americas between 1492 and 1550 to that of the six million Jews, as well as many Christians and homosexuals, in German death camps. Lacking a living cosmology, the modern era has sentimentalized religion and privatized it, locating it so thoroughly within the feelings of the individual that the dominant religious force of our civilization is that of pseudo-religion known as fundamentalism. (Matthew Fox, A Mystical Cosmology: Toward A Postmodern Spirituality, in Sacred Interconnections: Postmodern Spirituality, Political Economy, And Art, David RayGriffin (Editor), State University Of New York Press, Albany, 1990, pp 15-16).

Buddhist practice involving the use of mudrā, mantra and mandala are often regarded as the primary hallmarks of esoteric Buddhism. These practices originated in different stages and contexts in the history of Buddhism, but are nonetheless central to the formation of esoteric Buddhism as a historical phenomena (sic). In the more developed phase of esoteric Buddhism (sixth cent. onwards) mudrā, mantra and mandala became inextricably bound to the Three Mysteries (sanmi 三密), the unified “mysteries” or “secrets” of body (shen 身), speech (kou 口), and mind (yi 意) respectively. (Orzech, Charles, D., and Sorensen, Henrik, H., 6 MUDRA, MANTRA AND MANDALA in, Esoteric Buddhism And The Tantras In East Asia, edited by Charles D. Orzech (General Editor), Henrik H. Sorensen (Associate Editor), Richard K. Payne (Associate Editor), Brill, Leiden, Boston, 2011, p 76.)

Historically, China has generated more than one religious or quasi-religious world view. Confucianism and Taoism are the most remarkably 'religious' achievements of its native cultural heritage. But since these lack developed eschatologies comparable to those of Sanatana Dharma and Buddhism, I exempt them from consideration here. They exhibit little evidence of systematic use of the same three modes of sense-perception as purposefully engaged in meditative practice directed towards self-transformation. That is, they do not methodically employ these three phenomenal forms of sentience in the same manner as do Chinese forms of Buddhism, nor is their governing intention overtly soteriological. (In this connection see Bokenkamp, Stephen R., Ancestors And Anxiety: Daoism And The Birth Of Rebirth In China.)

That said, there remain ostensible differences between the adoption of sentient modes in meditative praxes in India and China, and these are of genuine consequence to this study. I shall put that two of the Eucharistic miracle stories, those which deal with acoustic memory and optic memory, The Feeding Of The Five Thousand and The Feeding Of The Four Thousand respectively, refer obliquely to these two civilizations, and that an essential part of the Eucharistic theology of these messianic miracle narratives alludes to the use of mantra and mandala as a typology of the collective consciousness of these very civilizations of central and eastern Asia, viz. India and China. The preferences for one rather than the other of such forms of sentient memory, and hence the predilection for mantra or mandala are mirrored in the consequent variations of religious praxes which predominate in the variations of Indian and Chinese, esoteric Buddhisms respectively. The general inclination of Sanatana Dharma follows the use of mantra rather than mandala, or dharani rather than yantra. It is generally within China that we see the rise to prominence of Buddhist iconography and the concomitant deployment of mandala. This will become even more pronounced in those Asian cultures which, in their nascent stages borrow heavily from the Chinese. The Japanese is an obvious example, and Shingon Buddhism a case in point. It is difficult to discern a Buddhist culture in which the role of all three techne, mudra, mantra and mandala, have been more instrumental; and among these, one in which the use of mandala as a means of metaphysical if not 'theological' proposition has been more seminal.

That there are no larger geopolitical groupings on the planet than these cultures, defined as such at the broadest level, thus squares with a vital aspect of the Eucharistic miracle narratives, namely, the many thousands involved, as does the basic theological perspective of both narratives, namely, immanence. At the time of writing, the population of India is set to soon exceed that of China, although they will remain of comparable scale for some time. But the primary justification for such a typological extrapolation of the same two civilizations which equally marks their similarities and dissimilarities, must remain the conceptual analogues of acoustic memory and optic memory. These are, the conceptual forms of unity space : time and male : female respectively. That said, we nevertheless immediately encounter in their native languages the same marked option for one specific sentient mode rather than the other. The languages of the Indian subcontinent are oriented more in virtue of acoustic rather than optic sentience. Their scripted forms of 'the word' follows the phonetic ('acoustic') mode as the primary bearer of meaning. The obverse is true of Sinitic language forms. These demonstrate a marked predilection for the optic. So much so, that even where borrowings have occurred, such as that of the Japanese language from the Chinese, the meanings of these 'graphic' signs is frequently the same, in spite of the wide divergences of their 'phonetic' renditions of the same characters.

Differences within each notwithstanding, the 'obliqueness' of the references concerns the postulate that the aconscious, conceptual analogues of these conscious, perceptual radicals are, typologically determinative of group identities of the Buddhist world religions other than Christianity, as they evolved. The plausible indications that acoustic sense-percipience is for Indian expressions of religious consciousness what optic sentience is for the corresponding Sinitic forms, must ultimately stem from their given respective derivations: the conceptual form of unity space : time for acoustic memory, and that of male : female for optic memory. Thus I am arguing that this establishes the basis for any pervasive Indian penchant for mantra, in both of its major religious traditions, Sanatana Dharma and Buddhism, just as the same relation between the anthropic category, male : female and its conscious, perceptual equivalent, optic memory, is instantiated in the evolution of visualization techniques as a hallmark of Sinitic Buddhisms.

Language, or to use the term favoured by the apocalyptist, 'tongues', are highly instrumental in forging collective identity, and the disparity in this case is outstanding. Such a remarkable divergence between the two as demonstrated in their preferential adoption of either means has indeed shaped the varieties of Buddhisms of both 'societies' taken as wholes. It will concern us in positing a Christian approach to mantra, mudra, and mandala; that is, to 'the three esoterica', since I contend that all three are equally constituents of a Christian meditative techne. These contemplative techne adopt the clearest disclosures in the gospels that the sense-percipient manifold of the body is a primary revelation of the deity; that is, these modes acoustic, haptic and optic, respectively correspond analogously to 'the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit' of classical Christian theology.

The very same three forms of sense-perception are central to the Christian theology of immanence. And it is here, as is clearly announced in the title of the essay, that the emphasis lies. I have argued that the same three phenomenal forms of sentience are the primary New Testament deposition of the doctrine of immanent Trinity, imago Dei, and theology of the Word (logos), first proposed in the P creation narrative. That is, that the theology of immanence accounts for the same three doctrinal tenets of Christianity, complementarily to its exposition in the creation narrative, and that their locus classicus as such, is the three Eucharistic miracle stories to be found in various measure in each of the four canonical gospels.

Further to the highly significant analogous rapport sustained by the two stories of 'beginning' and that of 'end', The Apocalypse belongs organically to this same syntax. These three texts are not only indispensable to one another in virtue of those same doctrines which are definitive of Christian theological understanding, they each characteristically espouse a specific mode of sense-percipience. Notwithstanding that they are all equally texts, and as such, manifests of the 'optic' word, as the result of their different emphases upon the three identities in God, The Transcendent, The Christ and The Holy Spirit, these three co-ordinated narratives, Genesis 1.1-2.4a, the messianic series, and The Apocalypse espouse that one specific mode of sentience which is proper to that identity. This follows from the doctrine of imago Dei. Their co-ordination is signalled by the arithmetical progression contained within the three narratives, as the iterated numerical symbol: 5-6-7. It orders them thus: The Feeding Of The Five Thousand - The Transformation Of Water Into Wine - The Feeding Of The Four Thousand; and so too, the sequence, acoustic, haptic optic, referentially to The Transcendent, The Son, The Holy Spirit. It functions recursively to the incipient threefold merism of scripture 'the heavens and the earth', notwithstanding the equivocal relationship to the final term, 'the earth', of both the gospel(s) and The Apocalypse. The same ambiguity surrounds the elision of 'The Son', as 'Son of man', and The Holy Spirit, and sorts with the doctrine of incarnation.

From that order, we see that mudra functions in media res of meditative practice. It stands between the transcendental character of the semeiacoustika, and the immanent nature of the semeioptika. That is, it mediates these antithetical semioses as the phenomenal, or sense-percipient exemplifications of identity : unity respectively. The three Eucharistic miracle stories which detail the forms of sentient memory, point to this as the arithmetical progression of the doubled ciphers: 5-6-7, reflecting the sequence of Transcendental-Christological-Pneumatological forms of sense-percipient memory, nevertheless, with reference to the organic coherence of sense-percipient imaginations, since each of the Eucharistic ('feeding') miracle narratives is complemented by a miracle story dealing with its counterpart according to the bifurcation of the space : time continuum. This is assured by their configuration as chiasmos.

A great range of opinion as to the interpretation of the term “mudrā” exists among authorities in the field of Buddhist iconography. Most of them converge toward a dominant idea contained in the original word: that of a hand pose which serves as a “seal” either to identify the various divinities or to seal, in the Esoteric sense, the spoken formulas of the rite. Coomaraswamy calls the mudrā “an established and conventional sign language”; Rao, “hand poses adopted during meditation or exposition”; Woodward, “finger-signs.” The translation in the Si-do-in-dzou is “geste mystique”; in the Bukkyō Daijiten, “the making of diverse forms (katachi) with the fingers.” Soothil defines them as “manual signs indicative of various ideas.” According to Getty, the mudrā is a “mystic pose of the hand or hands.” According to Eitel, “a system of magic gesticulation consisting in distorting the fingers so as to imitate ancient Sanskrit characters, of supposed magic effect.” The use of mudrā was introduced into Japan by Kōbō Daishi, and they are used chiefly by the Shingon sect. Franke proposes as a translation of mudrā Schrift (oder Lesekunst); Gangoly, “finger plays”; and last of all Beal, “a certain manipulation of the fingers ... as if to supplement the power of the words.” (Sanders, E., Dale, Mudra: A Study Of Symbolic Gestures In Japanese Buddhist Sculpture, Bollingen Series LVIII, Pantheon Books, New York, 1960, p 5.)

All of these interpretations may be summarized by the following categories:

1 seal (and the imprint left by a seal); whence, stamp, mark (in a general sense or the mark made by a seal), piece of money, etc.;

2 manner of holding the fingers;

3 counterpart (śakti) of a God.

At first glance, the three groups would seem to be quite distinct from each other. But Przyluski points out a most interesting connecting thread which unites them. Beginning with the idea of “matrix,” which he compares to a mold used for the printing or stamping of objects, he establishes a relationship between meanings 1 and 3. This is, in effect, the one which exists between the matrix of a woman in which is formed the embryo of the child she will bear, and the seal which impresses on the piece of clay its form or design. The same bond exists between the second meaning — i.e., symbolic gesture —and the other two, if one accepts that the position of the hands constitutes, to a certain extent, a mystic seal.Among the various meanings of the word “mudrā” in Sanskrit, the idea of sign as a seal is predominant in Esoteric thought. This notion crossed the frontiers of India with the vajrayāna and spread to China and later to Japan. In effect, it was by the Chinese word yin (Sino-Jap. in), “seal,” that the first translators were likely to render what seemed to them the dominant meaning of “mudrā” in the canonical writings. Thus it is that the diverse compounds designating mudra which are frequently met with in Sino-Japanese compounds all contain the vocable in. Among the most important are shu-in, kei-in, mitsu-in, sō-in, in-gei, in-sō, and simply in. On the other hand, certain authors or translators, anxious to note the Sanskrit word more precisely than the single ideogram in would permit, used Chinese characters phonetically in an attempt to reproduce the syllables “mu-da-ra.” (Ibid p 7).

To these two meanings of “in” - gesture and symbolic attribute - may be added finally that which designates even the mystic formulas (dhāraṇī) and the images of the Buddha. It is a matter then, with respect to the Sino-Japanese term, of a phenomenon of extension analogous to what has been noted for the Sanskrit term. Just as the notion of matrix is a connecting thread binding the various meanings of “mudra,” the idea of sign binds the three significations of “in”:

1 symbolic gestures of the hands used as “seals,” which guarantee the efficacy of the spoken word;

2 the symbolic objects, as well as the images and the statues, which are used as “marks of identity”;

3 dhāraṇī, spoken formulas, which “seal” the magic of the rites. (Ibid p 9).

There are six stories of healing miracles in the gospel of Mark, which advert to the structures of the perceptual conscious and perceptual aconscious. These announce haptic consciousness in these orders, conscious memory, and aconscious imagination, we may first note here, since I am arguing for the centrality of haptic sentience in communication, as in semiosis. That is, if we accept the organic syntax of the aforementioned three textual traditions foundational to Christian theology, the role of haptic consciousness as pivotal to both acoustic and optic semioses follows legitimately. Two texts from the series of twelve healing miracle stories contained in the gospel of Mark remain standard and classical depositions of the two forms of haptic sentience for that series. In the messianic series, The Transfiguration and The Transformation Of Water Into Wine function likewise. That is, they denote as categoreal components of consciousness, both haptic imagination and haptic memory respectively. I cite the healing miracle narratives in full here; they are a welcome overture to the more theologically extensive narratives which begin and end the series of six messianic miracles:

And a leper came to him beseeching him, and kneeling said to him, "If you will (e)a\n qe/lh?v) you can make me clean." Moved with pity, he stretched out his hand and touched him, (e)ktei/nav th\n xei~ra au)tou~ h(/yato) and said to him, "I will; (qe/lw) be clean." And immediately the leprosy left him, and he was made clean. And he sternly charged him, and sent him away at once, and said to him, "See that you say nothing to any one; but go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded, for a proof to the people." But he went out and began to talk freely about it (h)/rcato khru/ssein polla\ kai\ diafhmei/zin to\n lo/gon) and to spread the news, so that Jesus could no longer enter a town, but was out in the country; and people came to him from every quarter. (Mark 1.40-45).

Again he entered the synagogue, and a man was there who had a withered hand. And they watched him, to see whether would heal him on the sabbath, so that they might accuse him. And he said to the man with the withered hand, "Come here." And he said to them, "Is it lawful on the sabbath to do good or to do harm, to save life or to kill?" (a)gaqo\n poih~sai h)\ kakopoih~sai, yuxh\n sw~sai h)\ a)poktei~nai;) But they were silent. And he looked around at them with anger, grieved at their hardness of heart, and said to the man, "Stretch out your hand." He stretched it out, and his hand was restored. The Pharisees went out, and immediately held counsel with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him. (Mark 3.1-6).

Thus even though these stories both address the perceptual pole of consciousness, they distinguish between haptic imagination as virtually transcendent, the topic of the first narrative, and haptic memory as actually immanent, the subject of the second. This is due to the recapitulation of the paradigm transcendence : immanence within each polarity; the conceptual forms of the creation narrative, and the perceptual forms of the messianic series. The effect of the leper's action, which occurs notably in spite of the injunction to secrecy, another secondary marker of transcendence, is the restriction it places upon Jesus. Luke more or less maintains Mark's conclusion, but he emphasises Jesus' isolation. Transcendence is routinely conveyed in terms of privacy as opposed to publicity. This is perfectly intelligible in light of the Christological conceptual category, mind.

But so much more the report went abroad concerning him; and great multitudes gathered to hear and to be healed of their infirmities. But he withdrew to the wilderness and prayed. (Luke 5.15-16, emphasis added.)

We find references to touch both before and after these two narratives:

Now Simon's mother-in-law lay sick with a fever, and immediately they told him of her. And he came and took her by the hand (krath/sav th~v xeiro/v) and lifted her up, and the fever left her; and she served them. (Mark 1.30-31).I am discounting this particular text as a member of Mark's tally of just twelve healing miracle stories largely on account of its extreme brevity, and because it blends seamlessly with a summary of healing (1.32-34). The actual summary is in fact longer than the pericope concerning the individual woman, and is followed only by A Preaching Tour (vv 35-39), leading directly to the first of the two pericopae cited above. There is a similar healing summary just after the second narrative, The Man With A Withered Hand:

And he told his disciples to have a boat ready for him because of the crowd, lest they should crush him (i(/na mh\ qli/bwsin au)t/n); for he had healed many, so that all who had diseases pressed upon him to touch him (w(/ste e)pi/ptein au)tw~? i(/na au)tou~ a(/ywntai o(/soi ei]xon ma/stigav). And whenever the unclean spirits beheld him, they fell down before him and cried out, "You are the Son of God." And he strictly ordered them not to make him known. (Mark 3.9-12, emphasis added.)These references are indicative of haptic sentience as the precisely Christological, perceptual elements of consciousness. There are other healing miracle stories in which Jesus touches someone, which are not related to haptic sense-perception: The Deaf And Dumb Man (7.32-37), and The Boy With An Inclean Spirit (9.14-29) fall into this category. Also, The Haemorrhagic Woman (5.24b-34) portrays that figure as touching the garment of Jesus. But neither is this narrative about the percipient mode of touch. The use of somatic-haptic motifs in healing and other narratives in the gospel thus confirms haptic sentience as that specifically Christological mode of sentience, and the gospel itself, as centred upon the identity of 'the Son' rather than that of either Transcendence ('the Father') or The Holy Spirit.

Thus in keeping with Markan economy, we have just two stories which deal in turn, with each of the three modes of sense-perception, and these are ordered according to the intelligible, categoreal division between perceptual memory and perceptual imagination. Their division as such underlines a definitive Markan preoccupation, the conceptual form of unity space : time. Another remarkable healing miracle story in which touch plays such an important role is Jairus' Daughter (Mark 5.21-24a, and vv 35-43). Its description is strangely reminiscent of the wording used in the story of Simon Peter's mother-in-law:

Taking her by the hand (kai\ krath/sav th~v xeiro\v tou~ paidi/ou) he said to her, "Talitha cumi"; which means, "Little girl, I say to you, arise." (5.41).

The hand, clearly denoted in the second of the miracle stories cited, is the semeihaptikon of haptic memory. It is the means by which that particular element of mind, haptic memory, is represented by itself to itself. This reflexive representation is linguistic and communicative in nature. We may not know other minds, but we may see and feel and know that other bodies are constituted as is our own body in that they have hands. The self-representation of haptic memory in the mind is a common denominator to human persons, and so forms an important part of the basis of communication. The hand is not alone in this. I have previously argued for the comprehensive patterning of a systematic means whereby all radical components of mind, both conceptual and perceptual, are distinguishable as tangible members of the body, and that this is an essential part of the healing miracle series in the gospel of Mark. But neither the notion of embodied cognition, nor the equally important one of a Christian theory of language concerns us here. The purpose of this essay is to establish the rudimentary features of a praxis which draws upon techne utilised in Buddhist meditation and that of Sanatana Dharma, mantra, mudra and mandala. Mudras are used also by Jainas.

The immediate utility of the hand for Christian meditative practice rests upon the fact that the fingers contain just twelve phalanges. I do not include the thumb in this count. Only two of its joints are phalanges, the third is considered a metacarpal. If we include the thumb with the four fingers, the final number of phalanges is 14. This readily corresponds formally to the two sevenfold serial narratives, of Genesis and the gospels, since they each contain an outstanding seventh element. In the abstract the hand replicates a reticulate of 4x3 units. That is, the four fingers consist equally of three phalanges: proximal, medial and distal. We might just as readily render this in terms of its wholes, as three of one axis, and four of another, so that the hand just as easily embodies the heptad. And if we include the two most clearly articulated phalanges of the thumb, the total is 14. These figures, 7 and 14, no less than 12, occur with remarkable insistence in biblical literature. I shall return to the issue of the enumeration of the phalanges of the thumb directly in relation to the mandala and the hoshen.

Again, in the abstract, the paradigm of the hand as a network or web, and as the basis of the mandala in its simplest rendition, reminds us of Indra's net. Although it does not consist of exactly twelve components, it is often conceptualised as a three-dimensional nexus of joints, with a jewel at each vertex or node, similarly to the hoshen. (See Rajiv Malhotra, An Introduction To Indra's Net). The jewels reflect one another as tokens of interrelatedness. Both the hoshen and Indra's Net are points of comparison and departure, for neither engages the dodecaphonic series, which semiologically expounds the relations obtaining between the twelve categoreal entities of the Christian revelation concerning consciousness or mind. I will contend that this, the acoustic semiosis, referred to in The Feeding Of The Five Thousand, surpasses both of these metaphors in this as in other respects. Nor shall I develop any further, the physical consonance of the hand and the hoshen, since it is foremost a visual symbol, and one largely ill at ease in the Judaic tradition, as I explain below. The final reiteration of the hoshen occurs albeit in a new configuration in The Apocalypse, there as a constituent in the structure of the New Jerusalem. In just which context, that of Christian Pneumatology, it is indeed much more at home.

The dodecadic structure of the acoustic semiosis, its foremost and simplest morphological property, is consonant with the same format. Western music, and indeed Christian music in the west since the birth of musical notation, has employed sevenfold and twelvefold series in both its modes and its diatonic scales, and we see both configurations in the narratives. The P creation series and messianic series are both ultimately sevenfold, even while they clearly demonstrate other mereological forms. The structure of the four fingers immediately offers itself as a haptic-somatic manifest of the pattern 3 : 4, which recurs in both narrative cycles, 'beginning and end', focusing upon identity and unity respectively. Moreover both semioses, the sixfold-sevenfold optic, and sevenfold-twelvefold acoustic semioses, complementarily dispose the analogous rapport between the six conceptual and six perceptual components of consciousness according to various relations obtaining among them. These twelve radical categories are configured in the basic disposition of the four fingers of the hand. When viewed in the abstract, it comprises two axes, juxtaposed at right angles to one another: the four fingers each consisting of three phalanges; and the three phalanges themselves, distal, medial and proximal, taken in isolation from one another, recurrent in each of the four fingers. This establishes the basis of the mandala: a two-dimensional reticulate of 3x4 vertices. The juxtaposition of the two axes reveals that of disjunction and conjunction, in keeping with the presentation of the modes of antithesis in the P creation narrative, and the doctrine of external and internal relations, and their ensuing relation.

The practice of mudra then, marks an ideal place to embark on more wide-ranging contemplative exercises. Their primary and immediate source is the gospel, because of the congruence of the dodecad with the morphology of the optic semiosis and with the acoustic semiosis also. The repetition of the pentad and heptad in the two narratives of miracles of loaves certainly alludes to their summation, since the numerals both enumerate the same entity, the provision of initial loaves. And of course the dodecad features in the first of these as numbering the baskets containing remaining portions of the meal. So we may not ignore the fact that the dodecad is immediately embodied in the constitution of the four fingers. Removing the thumb from consideration, the full number of the phalanges amounts to just twelve. In accordance with this, semeioptika are reduced to just six in number. The legitimation for which rests upon the incidence of the hexad in both Christologies, Transformation Of Water Into Wine and Transfiguration, and the obvious fact the the Sabbath and Eucharist stand apart from their respective series. The tradition of accounting for the visible hues in the west stems from Newton, whose motive in their sevenfold enumeration stemmed from his attempt to co-ordinate them with the seven tones of the diatonic scale. The semeioptika as theologically representative of intentional modality, always involve the repetition of one of the six elementary hues. This iteration signifies the occurrence of one of the four, conscious modes of intentionality.

The children pictured in the following illustrations are practising Anjali Mudra, also known as Nebina Gassho in the Japanese, Shingon Buddhist tradition, or simply Gassho. This is an ideal beginning for the practice of mudra. Its current use in Christian liturgical practice is widespread and ancient. Its practice is equally widespread and even more ancient in Buddhism and Sanatana Dharma.

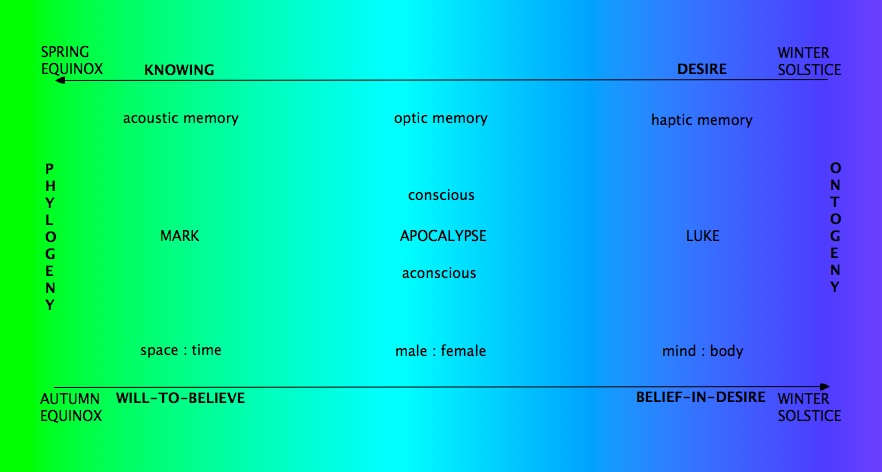

Known also as Hridayanjali Mudra, or Namaskara Mudra, this mudra is thus not exclusive to Christianity. Where Christian mudra meditation distinguishes itself from other traditions in which it is employed however, is in that it must signify the division into four architectonic elements of mind (logos), according to their analogously formed conscious and aconscious components. In describing these four dyadic components of mind as 'architectonic', I mean to emphasise the pervasive or ultimately general nature of the canonical occasions of intentional forms to which they give rise: desire, knowing, will and belief, and the aconscious formulations with which they are combined analogously: belief-in-desire, will-to-believe, knowledge-of-will and desire-to-know respectively. These four moments mark the four tipping points of the annual cycle, the two solstices and the two equinoxes, such that one member of each dyad signifies the diurnal interval, and its analogue, the nocturnal interval. As for the relation between mind itself and time, I am not referring merely to a developmental psychology, the necessary by-product of the growth and development of the actual body, during its passage through exceptionally clearly framed phases of life, such as we find outlined in the Dharmasutras and Ashram Upanishad. Nor merely do I refer to an evolutionary psychological understanding of the accord between time and the development of higher consciousness, ultimately reached in humankind, with the final compact between belief and the desire-to-know, signifying the summer solstice. I am referring also to the essential compact between temporal passage and ultimately the death of the body and the life of the soul as given in The Transfiguration.

These radically fourfold, architectonic or infrastructural aspects of the conscious-aconscious correspond to each of the four fingers in accordance with their representation of the four gospels. The particular accord of each gospel with a specific finger regards the difference in comparative lengths of the fingers, as signal of the greater or lesser duration of (day)light throughout that season of the year. The binary incarnate in the bilateral symmetry of the body generally, and of the hands in particular thus avails meditation on the nature of mind as twofold. Its twofold aspect, that of the conscious and aconscious structured in analagous rapport with one another, should be exercised in mudra practice according to left-handedness or right-handedness. Thus it does not matter which hand signifies which order, conscious or aconscious. This will depend on handedness in the practitioner. If left-handed, use the left hand to mark the conscious; if right-handed, use the right hand, and so on. This mudra as meditative practice concentrates upon the nature of wholeness given in the variety of relations among mental structures, analogously to the structures and passage of time. It also stands representatively of the two antithetically and simultaneously related topoi, the two hemispheres of the earth itself. That is because of the simultaneity of the antithetical equinoxes in the hemispheres, and the same simultaneity of the two solstices. The figure four in all three texts, creation story, messianic series, and The Apocalypse, routinely signifies immanence, and the earth.

We may use the index to designate Mark; the middle finger John; the ring finger Matthew, and the little finger Luke, in accordance with the progression of seasonal quaters marked by The Apocalypse: letters~spring; seals~summer; trumpets-autumn; bowls~winter. It would be both viable and possible to interchange the index and fourth fingers in terms of their representations, given their comparable lengths. The same cannot be said of the contrast between the middle and little fingers. I am basing these principles of Christian mudra on the variations in the ratio of day and night at the two solstices and two equinoxes congruently with the role of time and the metaphorical value given to the light : darkness motif, as well as that of day : night in the creation story, in league with the extensive reach of the actual fingers themselves; that is, with their given lengths. But this is not to derogate all three gospels other than that of John in relation to it.

These sevenfold series are referential not just to the four gospels, but to to specific Christian confessional traditions which exemplify them, and moreover to world religions which do the same. If we use the index finger representatively of autumn~Matthew, then the pattern index-middle-ring-little finger(s) restates the seasonal sequence in reverse, beginning with Luke~winter and so on, ending with spring~Mark. Either format, that is, either way of assigning a specific finger to Mark as to Matthew, is legitimate for the purposes of mudra. The salient feature of mudra in its Christian usage is its evocation of the gospels vis-à-vis their mirroring of the relation between time and mind, and the co-ordination of the conscious and aconscious orders of the latter, signified by the two hands. It goes without saying that it is not so much the actual gospels as texts themselves, represented by the disposition of the hand, which are intrinsic to the development of meditative technique, but the specific forms of intentionality which subserve their theological ends.

Since I am right-handed as is the majority of the human population - there are some surprising exceptions in the sub-human realm - I distinguish my right hand from the left according to the distinction of the two orders of those same intentional forms, conscious from aconscious respectively. But I repeat, one should adapt praxis for left-handedness, and reverse this concept. Ambidexterity is evidently exceptionally rare, and is usually accompanied by a preference for a particular hand, the so-called 'dominant hand'.

Wholeness, or unity, so to speak, is central to the theology of immanence. The fourfold cipher, readily visible in the format of the gospel(s) and incarnate in the hand, is its token. The other cipher for unity, is seven. We find both featured in The Feeding Of The Four Thousand, the Pneumatological, Eucharistic miracle story. The lattice or reticulate which the four fingers of the hand constitute, are the somatic manifest of these two ciphers. The framework which they form, is essentially a reticulate whose basic configuration uses the ratio 3 to 4. This stands emblematically of the relation of transcendence and immanence, the categoreal paradigm first announced in Genesis 1.1, 'the heavens and the earth', and is consonant with the three Trinitarian-Christological titles: 'beginning and end, first and last, the Alpha and the Omega.' The product of these two numbers is 12, and their sum is 7. These figures are recurrently significative in the biblical literature, especially in the Eucharistic miracle stories and in The Apocalypse. I shall say more concerning the form of the hand and mudra in relation to mandala, and to mantra in what follows.

The notion of the cipher four as a token of wholeness concerns the relation of the world to God. I have described this relation as internal. One meaning of which is that the world affects God. God is not immune to what transpires in the world, and effectively, the unity (wholeness of identities) in God, depends on sub-human and human consciousness. This makes the doctrine of intentionality an essential aspect of logos theology, and assures the definition of the soteriology-eschatology specific to each of the four gospels by the same means. That is, it adduces the use of a functional definition of mind a propos of the difference of one evangelical perspective from another. Thus in the case of Mark for example, the governing intentional modes are knowing and the will-to-believe. Intentional modality rather than any supposed amalgam of taxonomical components of consciousness is what guarantees the oneness of God. That is, the radical, taxonomical entities responsible for the intentional modes, knowing and will-to-believe in their canonical occasions, acoustic memory and the conceptual form of unity space : time respectively, are not conducive to unity. The occasions or instances of the same two intentional modes, the first example, knowing, throughout the entire range of perceptual radicals, and the second, the will-to-believe throughout the entire spectrum of conceptual radicals, is what ensures the internal relatedness of 'the world' to God, as well as the value of our own lived experience and that of creatures other than humans, to God.

The Anjali Mudra is remarkable in its representation of this fact. The division of consciousness into conscious and aconscious orders, signified in this mudra by the two hands joined together, insists on the fact that conscious intentional processes, such as knowing, are functional throughout both orders, and conversely, that aconscious modes, such as will-to-believe are likewise operative irrespective of this same division. Each of the six perceptual categories is capable of an instance of all six perceptual modes of intentionality, regardless of the designation of either the radical itself or the mode itself, as conscious or aconscious in its canonical occasion.

The same applies to the conceptual pole. An example of the latter is given by the soma (mind : body) itself. This is classed as a conceptual form of unity. It is a second order conceptual form, not a pure conceptual form, but an idea or concept which imitates a percept, the percept in this case being haptic memory, such that we speak of it in terms of virtual immanence. The intentional mode which devolves from this conceptual form, is belief-in-desire. That is to say, the soma is the defining occasion of what we mean by this form of intentionality; it alone is the defining occasion of that mode of intentionality. Both the radical, or categoreal entity, soma, and the intentional mode which it produces, belief-in-desire, are by definition, aconscious. The conscious mode, which in some sense performs antithetically to belief-in-desire, is belief simpliciter, and is native to mind, the pure conceptual form. From this radical of pure transcendence the intentional mode belief is born. Thus we may say that the radical component and the intentional mode of which it is the defining occasion, belief, are both conscious. Belief can and does function as a mode of the soma, in spite of the fact that belief is classified as a conscious form of intentionality, and the conceptual form soma is classified as an aconscious categoreal entity. This is an example of what is meant by affirming that all six modes are operative throughout all six of the categoreal entities defined at the first level, as either conceptual or perceptual.

In conjunction with this mudra we may use the three permutations of the threefold formula, which iterate that paradigm, 'the heavens and the earth'. These are: 'beginning and end', 'first and last', and 'The Alpha and The Omega'. They are perfectly fitted to replace the address to the Holy Trinity: 'The Father, The Son, and The Holy Spirit', used in the Gloria, and have the advantage of avoiding any charge of patriarchalism one may level at the latter. This form of address may be used at the beginning of meditation with the Mudra of Veneration:

'Glory to God; the beginning and the end, the first and the last, the Alpha and the Omega.'The same Trinitarian titles, each tripartite in itself, maintain three references. They indicate: (1) instrumental relations; (2) relations of prevenience-supervenience; (3) and the analogous relations which bespeak the one-to-one correspondence between the two categoreal, polar entities, conceptual and perceptual and their corresponding modes of intentionality. In all three cases the meanings of the initial and final terms are resolutely followed.

(1) The four instances of instrumental relations are from will~to~belief (diurnal spring equinox~summer solstice); from desire-to-know~to~knowledge-of-will (nocturnal summer solstice~autumn equinox); from will-to-believe~to~belief-in-desire (diurnal autumn equinox~winter solstice); and from desire~to~knowing (nocturnal winter solstice~spring equinox).

(2) Relations of supervenience are those already indicated as the passage from a conative (causative) and distal mode of intentionality, to a proximal mode: desire-to-know~to~knowing; desire~to~knowledge-of-will; will-to-believe~to~belief; and will~to~belief-in-desire.

(3) Analogous relations denote the fact that one of the two members of each dyad signifying the tipping point is the final (temporally proximal, cognitive) intentional mode of its class or taxon, and the other is the initial (conative and temporally distal) mode; for example, belief is a final (proximal) and cognitive form of intentionality, but it is underpinned by desire-to-know, which is conative, and the initial member of its class.

In each of these three cases, there is an initial term - 'beginning', first', 'Alpha' - and a final term - 'end', last', 'Omega'. The above form of the Gloria therefore comprises the temporal relations between intentional modes when contemplating the annual cycle, and the fourfold form of the gospel. We need not pursue these details here. But the structural reach of the semantic of these titles should be borne in mind. They are nothing if not comprehensive. I reproduce the following mandalic iconography which summarises the four tipping points analogously to the integral relations obtaining between the gospels as entailed by the doctrine of intentionality pursuant to the theology of the logos.

Anjali Mudra joins the hands in an attitude of respectful acknowledgement. It can therefore stand as homage to the gospels themselves as the deposit of faith. We need not envisage them as the products of individuals, although in the cases of Luke, and probably John for the most part, this seems legitimate. That is, the mudra need not, as for guru yoga, be an act of veneration towards another human person, or yet again, towards the texts themselves as texts. What is of prime importance as far as homage or veneration is concerned is given in the subject: the word of God, that is the person of Christ. Mudra are essentially bound to this person ('identity') as are mandala to The Holy Spirit, and mantra to The Transcendent.

Having been celebrated as fundamental to a natural theology since earliest times, and having been recorded in a variety of archaeoastronomical monuments in an equally variant distribution of time and place, the division of the year is marked by four seasons, each amounting to approximately 13 weeks; those of spring, summer, autumn, winter. Respectively, these express the dynamics of dark to light - winter solstice to spring equinox; light to light - spring equinox to summer solstice; light to dark - summer solstice to autumn equinox; dark to dark - autumn equinox to winter solstice. The Letter To Nagarjuna records these as types of humans, personality types, but his reference lacks any evident analogy to the fourfold division of the year as such, opting instead for a single ideal:

There are four kinds of persons (pudgala): those that go from light to light, those that go from darkness to darkness, those that go from light to darkness, and those that go from darkness to light; of these do thou the first! (Nagarjuna's "Friendly Epistle", Journal Of The Pali Text Society, Translated by Heinrich Wenzel, London, Henry Frowde, 1886, stanza 19.)We shall say more concerning categoreal entities as the basis of a typology of personality, and hence, its relevance for Christian deity yoga. The role of identity in the theologies of transcendence supports such a strategy. In Nagarjuna's work, the figure light-to-light stands as exemplary of the ideal Buddhist. But Christian meditation employs all four seasonal figures since each is equally represented in the structure of the gospel, a structure which reflects the anatomy of mind itself. This is the rationale of the revisioning in The Apocalypse of the very four zodiacal symbols first delivered in Ezekiel 1 and 10. Its justification depends upon the doctrine of intentionality which defers in the first instance to the two narratives, Genesis 1.1-24a and the messianic series. Thus each of the four, dyadic configurations of intentional modes constituting the most radical aspect of the twelve categories vis-à-vis the temporal template of the year, is equally an analogous manifestation of the most radical structural features of mind. In just this respect the gospel as fourfold, comprehensively offers analogues both to the the phenomenon of world religions, and the fundamental varieties of Christian confessional stances, the various forms of both of which it recognises and affirms.

The epistemological status of the attributions concerning world religions and specific Christian ecclesial varieties contained in the following second table is typological, the content of which summarizes some of the relevant postulates concerning the series of seven seals for both ecclesiology and the Christian theology of religions. At the outset, it is necessary to make a logical and epistemological distinction between taxonomy and typology. Thus the first table essentially summarises the two primary depositions of the Christological, propositional content of faith: Genesis 1.1-2.4a and the messianic series, independently of the content and intent of The Apocalypse. Nevertheless, it includes the four Pneumatological components of mind, which remain the central Christological concerns of that book, and which are uniformly determinative of medial temporalities, and highly significant for the concept of temporal passage. This sorts with the irreducibly hybrid character of their corresponding modes of intentionality. These radical components of mind, and their ensuing intentional forms are already disclosed within the two serial catalogues, Days and messianic events. Like Christological and Transcendental intentional modes, they belong to both conceptual and perceptual poles of consciousness. But it is apparent from the mere fact that there are only four tipping points of the annual, temporal compass, to which the organic composition of the gospels conforms, that they differ remarkably from the four-eight radicals representative of the soteriological perspectives proper to each of the four gospels. It is precisely this difference which leaves the Pneumatological radicals of consciousness as the ambit of The Apocalypse, and which is responsible for the singular quality of that member of the canon when viewed in its syntactical co-ordination with the texts of Genesis and the gospels, the stories of beginning and end.

Consequently the Christological-Transcendental soteriologies of the gospels are remarkably consistent also in being premised on the four dyads which are other than Pneumatological. Pneumatology remains the concern of The Apocalypse, as is abundantly clear from its emphatic pre-occupation with the perceptual radicals, optic imagination and optic memory as well as the conceptual radicals, symbolic masculine and symbolic feminine. The central vision of the woman crowned, the war in heaven, and of the two beasts reinstate the conceptual Pneumatological radicals which are the analogues of optic memory and optic imagination. Thus the references to 'the beast from the sea' and the 'beast from the earth' the Pneumatological rubric Day 3, which is paired to that of Day 6, detailing the creation of the male and female humans, but also to Genesis 1.2; the description of the state antecedent to the creation, which mentions these same two elements, the sea and the earth.

The four sevenfold series of The Apocalypse are therefore formally and symbolically commensurate with the structure of the gospels. The two series of unnumbered visions in The Apocalypse, 12.1-14.20 and 19.11-21.8, certainly contain references of the kind which match the two sets of Pneumatological categories, optic memory : optic imagination, and symbolic feminine : symbolic masculine. (This reckoning excludes the text following the seventh bowl, the fulsome description of the fall of Babylon - 'the great harlot' (17.1-19.10). At this point the term ei]don recurs several times (17.3, 6, 8, 12, 18, 18.1). These uses all describe the same event, the destruction of Babylon, heralded in the seventh bowl immediately prior (Apocalypse 16.17-19). They therefore do not constitute a series of episodes differentiated from one another as do the events of the two unnumbered septets, and do not interfere with the validity of the two unnumbered septets as formally assignable to Pneumatology; yet another factor symbolically securing the relationship of The Apocalypse with the gospel.) In these sections of the work, which may well constitute its original core, we find ei]don ('I saw', emphasis added,) as recurrently as we do the formula myhl) rm)yw, ('[And] God said', emphasis added,) in the creation narrative, to which The Apocalypse stands as literary foil. It is true of course that each of the axiological affirmations is prefaced by a reference to sight: 'And God saw, that it was good.' (0)ryw, Genesis 1.4, 10, 13 et passim, emphasis added.) Unlike the speech act however, this is not the causative expression of God's will, and its location at the conclusion of each creative fiat is effectively precursive of the link between optic sentience and teleology-eschatology in The Apocalypse. The latter of course for its part contains many references to acoustic sentience; notably those of the series of letters and trumpets, which are nevertheless clearly linked to The Transcendent.

| CONSCIOUS MIND |

PURE

CONCEPTUAL FORMS - TRANSCENDENCE |

FORMS OF

MEMORY - ACTUAL IMMANENCE |

||||

| TEXT RADICAL CANONICAL INTENT. MODE SEASONAL ANALOGUE TEMPORAL ANALOGUE |

Day 2 space will summer 1 distal future |

Day 3 symblc. masculine will-and-believe summer 2 medial future |

Day 1 mind believe summer 3 proximal future |

Feeding

5,000 acoustic memory know spring 3 proximal past |

Feeding

4,000 optic memory desire-and-know spring 2 medial past |

Water

Into Wine haptic memory desire spring 1 distal past |

| ACONSCIOUS MIND |

FORMS OF

IMAGINATION - VIRTUAL TRANSCENDENCE |

CONCEPTUAL

FORMS OF UNITY - VIRTUAL IMMANENCE |

||||

| TEXT RADICAL CANONICAL INTENT. MODE SEASONAL ANALOGUE TEMPORAL ANALOGUE |

Walking

On Water acoustic imagination know-of-will autumn 3 proximal future |

Stilling

Storm optic imagination desire-to-know and know-of-will autumn 2 medial future |

Transfiguration haptic imagination desire-to-know autumn 1 distal future |

Day 5

space : time will-to-believe winter 1 distal past |

Day 6 symblc. feminine (male : female) will-to-believe and believe-in-desire winter 2 medial past |

Day

4 mind : body believe-in-desire winter 3 proximal past |

| GOSPEL - HORSEMAN |

JOHN - first |

MATTHEW - second |

LUKE - third |

MARK - fourth |

| SEVENFOLD

SERIES APOCALYPSE |

seals |

trumpets |

bowls |

letters |

| MODE OF

CONSCIOUS INTENTIONALITY |

to believe |

to will |

to desire |

to know |

| MODE OF

ACONSCIOUS INTENTIONALITY |

to desire-to-know |

to know-of-will |

to believe-in-desire |

to will-to-believe |

| SEASONAL

ANALOGUE |

summer |

autumn |

winter |

spring |

| TEMPORAL

ANALOGUE |

summer solstice |

autumn equinox |

winter solstice |

spring equinox |

| EXEMPLARY

TYPE WORLD RELIGION |

Christian |

Judaism(s) |

Buddhism(s) |

Sanatana Dharma |

| EXEMPLARY

TYPE CHRISTIAN CHURCH |

(Eastern) Orthodox |

(Roman) Catholic |

Lutheran |

Reformed |

The order of the first four seals as denoted by the semeioptika white, red, black green, (Apocalypse 6.2, 4, 5, 8), designates the seasons and their corresponding gospels: summer - John; autumn - Matthew; winter - Luke; spring - Mark. As signifiers, these are more important as well as more efficient than the zodiacal signs used in the initial vision of the four living creatures ('zoa', 4.6b). That the zodiacal signs historically have been attributed to different gospels by different authors is yet another reason to dispense with them as ultimately significant. The order presented in John's initial vision is remarkably at odds with the occurrence of the astrological signs in sequence, since lion-ox-man-eagle refers to Leo-Taurus-Aquarius-Scorpio, unless we take it refer to the precession of the equinoxes. (There are two zodiacal signs intervening between these successive signs in each case.) Moreover this order does not conform to the pattern established in Ezekiel 1.10: man-lion-ox-eagle, nor to that of Ezekiel 10.14, in which the order is 'cherub'-human-lion-eagle, just as these two orders in themselves are inconsistent. In all, the zodiacal signs are not semiologically important. That they point to the succession of the year viewed in terms of the two equinoctial and two solstitial seasons is enough. The same four zodiacal signs are not mentioned beyond the initial vision, although the living creatures are. The semeioptika therefore fulfill the task of delineating the gospels vis-à-vis the annual cycle.

The second table above read from left to right omits the four intervening ('medial', Pneumatological) elements, whose modes of intentionality are uniformly hybrids, and it follows the seasonal order beginning with the summer. This is also the order of the three numbered sevenfold series, seals, trumpets, and bowls, insofar as these replicate three quarters of the same quaternary. This follows the author's penchant for the figure four as signal of the earth and of immanence generally.

The series of letters which introduces the narrative is not numbered, and on this account comes last according to the pattern disclosed by the semeioptika as mentioned in the vision of the four horsemen. In a sense then, the work is arranged similarly to the fourth gospel which ends with a fishing expedition evoking the calling narratives, which the synoptists place at the start of their gospels. The end returns us to the beginning.

The deployment of colour terms, including the achromatic expressions 'white' and black', is illustrative of John's idiomatic penchant for visual signifiers, or what I am calling semeioptika. In assigning each horseman a differently coloured horse, John identifies each of the four living creatures in relation to the annual spatiotemporal compass. The visions of horses and the like in both Zechariah and John occur in tandem with the four cardinal directions, as well as the four tipping points of the annual cycle. Four angels are involved in the sealing, and similar expressions further display the author's penchant for the symbolic and theological value of that figure. (References to various fractions of quarters and thirds occur throughout the text. The description of the rider on the black horse mentions both 'a quart' (xoi~nic) and 'three quarts' (trei~v xoi/nikev, Apocalypse 6.6) according to certain translations. The term is a hapax legomenon; and does not denote literally a 'fourth part'. That fraction, 'a fourth' or 'quarter', does occur in the verse concluding the vision of the four horsemen: '... and they were given power over a fourth of the earth (e)pi\ to/ te/tarton th~v gh~v), to kill with sword and with famine and with pestilence and by wild beasts.' (Apocalypse 6.8b)).

The purpose behind the adoption of zodiacal imagery, once it had been given a legitimate scriptural warrant by Ezekiel, points to the temporal compass, that is, the annual cycle, consisting of four distinct tipping points marking the beginning and end of the four seasons. The concept of time looms large in John's consciousness. It is evinced by the resumption of thematic constructs from Daniel, another prophetic work in which temporality is a prevalent if not the dominant conceptual motif. The expression 'a time, times and half a time' occurs in Daniel 7.25 and 12.7 (LXX e(/wv kairou~ kai\ kairw~n kai\ h(/misu kairou; e)iv kairo\n kairw~n kai\ h(/misu kairou~) and recurs in Apocalypse 12.14 (kairo\n kai\ kairou\v kai\ h(/misu kairou~). The concept of time is evident also in the recurrence of the threefold distinction John forges between past, present, and future, which to some extent, he superimposes on the three Christological-Trinitarian titles; 'the beginning and the end', 'the first and the last', 'the Alpha and the Omega' (Apocalypse 1.4, 8, 4.8). The same threefold temporal division is twice applied to 'the beast' (Apocalypse 17.7-14).

Over time, the twelve zodiacal signs themselves, as measures of the equinoctial and solstitial tipping points, change. Thus the spring equinox is marked by each succeeding zodiacal sign in the circle, moving counter clockwise, every 'astrological age'. This is the result of the precession of the earth's rotational axis, and even though the complete cycle occurs once every 25,772 years, it has to be taken into account. Each astrological age endures for between approximately 2,000 and 2,500 years. Astrologers do not agree on the computations of astrological ages because there is no consensus as to whether these twelve ages are of equal or variable lengths. Of the four figures recorded in Ezekiel which John borrows, it is probable that the bull, the sign for Taurus, marked the spring equinox in the northern hemisphere during Ezekiel's lifetime.

Thus John's use of semeioptika avoids any confusion. The two sets of colour words, achromatic and chromatic, unambiguously denote the two sets of antithetical seasons, solstitial and equinoctial respectively, reinforcing the iconography of the four zoa as indexing the four gospels, and concomitantly their 'eschatological' reinscription in the four sevenfold series of The Apocalypse. The oppositional chromatic colour terms red and green used in the context of the first four seals, designate the two quarters which culminate in the equinoxes, autumn and spring respectively. The two different equinoctial diurnal-nocturnal measures are simultaneous in the northern and southern hemispheres. This binary also adverts to the gospels of Matthew and Mark respectively as their analogues. The further use of the achromatic, oppositional colour terms, white and black, designates the relation of the seasons ending in solstices, equally simultaneous in the two hemispheres. These specify the summer and winter respectively analogously to the gospels of John and Luke respectively. Hence these four colour terms in the description of the first four seals apply indirectly to the living creatures themselves, through the horsemen which they each call forth, and so fit the four septenaries as aligned with the gospels, and the gospels themselves as aligned with the fourfold annual cycle.

The serial order white-red-black-green operates analogously in two ways. Firstly, it delineates the series of heptads beginning with the seals themselves, the same series in which this order itself is put. Secondly, as analogues to the heptads, beginning with the last term, it delineates the four septenaries as they occur sequentially in the actual text. This means that the first sequence begins with the numbered heptads, and corresponds to summer (white - seals), autumn (red - trumpets) and winter (black - bowls), consecutively, thus highlighting the first. The second sequence begins with the last colour term, green, denoting the spring, and the series of unnumbered letters, which it thus isolates for consideration. (Both names mentioned a propos the rider on the green horse, 'Death' and 'Hades', recur in the introduction to the series of letters (Apocalypse 1.18)). In this way, the first two heptads, both highlighted, are grouped together. Together, they determine the two corresponding quarters of the solar cycle when the ratio of light to dark, day to night, is increasing. The same format is reflected in that the contents of the two remaining heptads are highly similar. The Apocalypse thus divides congruently with the two fundamental durations of the annual cycle marked by the dynamic ratios of light : dark and day : night. This sorts well with the logos theology to which both the Days series and messianic series are foundational.

These semeioptika also identify the four living creatures, and thus, the alignment of the gospels with the four clearly demarcated sevenfold series:letters; seals; trumpets; bowls. John's text is not only comprehensively intertextual, since it extensively encompasses portions of the Tanakh, and refers just as clearly also to the gospels. It is intratextual as well. Moreover, it subsists as a natural theology, since the overriding referent of the first four seals is the tetradic disposition of the annual cycle. In this respect, precisely as an ending, it complements the story of beginning, in which we first encounter the theological nexus between time and mind.

The tetrad is the most rudimentary and overarching form, the architectonic, of any typological personality theory, but it must include the reality of temporal passage from one tipping point to the next. It must account equally for the entire panoply of differing ratios between the diurnal and nocturnal intervals which occur repetitively throughout the years, in its analogical function; that of the disclosure of mind or consciousness, the Christological category par excellence. Indeed, if it is to function analogously to personality-typological theory, this pattern should be construed extensively as a spectrum, in keeping with the two semioses, acoustic and optic, which serve its semiological articulation and representation. Even in that case moreover, we must admit the overriding fact of continuous change; that is, the reality not just that 'persons' themselves are susceptible of change, which is itself reflected in the passage of the annual cycle; but also that any such construal of a spectrum from one to the other of its termini will allow for a vast, if not putatively infinite number of individual points, each indexing a 'type'. This bears upon the hermeneutic not just of the series of seals in The Apocalypse, but specifically upon that of the sixth seal, in which persons are collectively identified as belonging to 'tribes', just as it will bear upon the incidence of other twelvefold conceits in that same work.

The fingers of both hands joined together in the Anjali Mudra, mirror the analogical accord of four seasons, with the epistemological-psychological syntax of the gospels. We may then conceive of this mudra as equally observant of the four taxa, as well as of the specifically decisive and pivotal four moments which mark the epistemological-psychological basis of each one of the four gospels. In such a representation the final form of intentionality, is the determining factor. In all cases this is epistemic or cognitive, rather than conative, and denotes a proximal rather than a distal temporal domain. It is superodinate in its functional capacity over its counterpart, whether this be in the conscious or aconscious order. In other words, for example, just as the middle finger may answer to the fourth gospel John, insofar as its own evidently idiomatic and Christological concerns arise from the conceptual form mind, and the perceptual form haptic imagination, and moreover, from the two modes of intentionality deriving from these, namely belief, and desire-to-know respectively, so too it marks the passage of which Nagarjuna speaks; that of summer, the transition of 'light to light', as the increase in the diurnal interval relatively to its nocturnal counterpart. That is, it signifies the taxon of three pure conceptual forms and their concomitant three modes of intentionality.

Superordinacy is tantamount to entelechy. Superordinate intentional modes occupy the final phases of their respective taxa away from distal temporal domains towards immediate temporality; in short, the Sabbatical-Eucharistic now. Thus all superordinate members of their taxa, including those of the aconscious, belief-in-desire and knowledge-of-will, accomplish the inherent drive of the taxon itself, the acme of its intrinsic purpose in virtue of knowing or belief, and its accompanying impetus towards the present from either the past or the future. They are consequently cognitive or epistemic, and proximal rather than distal in their relation to the hic et nunc. Thus the four fingers of Anjali Mudra capably manifest both the transitions towards the four tipping points of the annual cycle, and the tipping points themselves as analogous to the various tenets of the theology of logos preserved in the doctrine of intentionality. They embody both the motion towards the consummation of the class of entities to which they belong, and that very consummation itself.

That each finger contains three phalanges coincides with the composition of each taxon as tripartite. This additional representation of the inherent momentum of the four taxa as belonging to the business of its given corporeal analogue, one of the four fingers, has certain ramifications for the prospect of the theology of religions announced albeit in its nascent form, in The Apocalypse. That this must necessarily be typological in nature ensures its connection with what has been said concerning personality theory, and the hermeneutic of the series of seals. The Anjali Mudra in Christian usage thus returns us to consideration of the annual cycle, and the all-encompassing nature of the gospel; its everlasting relevance for all times and all places, and its embrace of all living entities in salvation.

We should bear in mind, given the use of Anjali Mudra in both traditions other than the Christian, that is, Sanatana Dharma and Buddhism, the consideration which these afford to animal life. The immanence of God within the consciousnesses of subhuman animals is a prime factor in such consideration. Animals are pertinent and sympathetically treated subjects in both creation narratives; several healing miracle stories; the Lukan infancy narrative and several parables; and consistently throughout The Apocalypse. There too, The Son is routinely referred to as "The Lamb". The same theme, the value of animal life to God, is sounded in many Psalms. The following image is presented in the same spirit, and in order to emphasize that the Christian worldview too, enjoins such consideration.

The dispositional consonance of human hand with the mandala in its simplest rendition in no uncertain sense rescues it from mere abstraction, and distinguishes between two fundamental temporal perspectives, of which its abstraction to the form of a reticulate itself is incapable. These are not those of linear and cyclic, any more than they are those of past and present. They are reiterations of the categoreal radicals complete with a variety of their corresponding intentional modes, including the hybrid forms of the same, viewed now as synchronic and now as diachronic. That is to say, as both sub specie aeternitatis and sub specie durationis respectively. The hand embodies the semiological expression/representation of both harmonic intervals and melodic intervals. Harmonic intervals are sounded or sung, simultaneously; melodic intervals are sounded or sung successively. Harmonic intervals as a group, are expressed in the relatedness of the distal, medial and proximal phalanges of the four fingers and so they have four constituents. This is not to say that the nomenclature for these groupings is necessarily applied to the intentional modes in question. It does not follow that the distal phalanges always signify distal intentional modes. But we shall come to this point later. Melodic intervals as a group are reckoned on the actual four fingers themselves, and so they have three constituents.

Their differentiation is exclusive to acoustic semeia; which is to affirm that it is insusceptible of mathematical representation. There is no means other than by the acoustic semiosis of its expression/representation. In other words, the theological exposition of the relation of mind and time is peculiarly the burden of the acoustic semiosis, the reason for attributing to the gospel of Mark, the intentional modes will-to-believe and knowing, since for that gospel both categories, space : time, and acoustic memory, are of pre-eminent moment.

We might have expected the former, transcendental in kind, to emphasize the triad, and to consist of three units, and the latter, immanent in kind, to consist of four, highlighting the tetrad. But the opposite occurs. It is not the composition of the actual relations, their number of components, but rather the total number of related forms so constituted, arising from the thoroughgoing interdependence of the twelve semeia, and the express semiotic/semantic relation of the ciphers 3 and 4 indicatively of temporality comprehended in these two disparate ways, as of their intrinsic relation. For there are indeed three comparable organic arrangements of synchronic semeia, configuring transcendence; each of which has four parts or components. Just so, there are four comparable organic arrangements of diachronic semeia; each of which has three parts or components. The structure of the human hand viewed in the abstract, as a reticulate or matrix composed of the intersection of horizontal and vertical axes, four of one kind, three of the other, intersecting at twelve points, recreates the substructure of the mandala as the expression of mind and time in their given togetherness. (The latter do not correspond to the simple organization of the four taxa, except in one mandala. I shall refer to this as the Markan mandala, since it emphasises for contemplation, the two modes, knowing and will-to-believe, in their canonical occasions.)

Elementary radicals of mind expressed in terms of their relation sub specie durationis conform to the theological delivery of the two primary narratives, creation and salvation, which groups them according to the fourfold taxonomical principle. Thus as successive, they mark the (four) transitions from element to element within either polarity, conceptual or perceptual, independently of the ordered dichotomy conscious, aconscious, since as already noted, conscious intentional modes may inhabit aconscious taxonomical radicals, and vice versa; aconscious categories may instantiate conscious intentionality. This organization is obedient to the first level distinction made by the two narratives, creation and salvation, where once again we find the Trinitarian formulae as categoreal paradigm, 'the heavens and the earth'. The four markers of successive ('diachronic') temporal passage, and their three constituent Christological (philosophical-psychological) components as logically contiguous (continuous), incarnately exhibited by the four fingers, are expressed/represented by three whole tones in every case. These are uniformly determined as continuous, that is, successive. The passage from one to the next is uniformly semiologically articulated by the interval of a whole tone.

This is not so for the same components viewed in terms of their relation to one another sub specie aeternitatis. Here there are three groups of four semeiacoustika, signified by the four distal, four medial, and four proximal joints of the four fingers. These necessarily combine the two poles, conceptual and perceptual, as expressed/represented by both whole-tone scales. The components in all three cases are not simply of one kind, conceptual or perceptual. Nor does the interval of a single whole-tone occur in their semeiacoustikal expression. The basic pattern has already been put: it consists of the major triad with the addition of the minor third below the tonic of the same. That is, the minor/major seventh harmonic interval. (The major/minor seventh also occurs as implicated in the same configuration.) This combines in each case, the conative and cognitive modes of intentionality of all four of its taxonomical permutations: conscious conceptual; conscious perceptual; aconscious conceptual and aconscious perceptual.

The concept of harmony will play a leading role in the exposition of what I believe Whitehead means when he refers to as 'God's primordial nature'. Leibniz uses the phrase 'pre-established harmony' to mean something very similar: viz. the ideal or potential established for the optimization of value reflecting God by his creatures. The phenomenon of harmony is the single great advantage that the acoustic semiosis enjoys over mathematics in its capacity to reveal consciousness to itself. It is a manifest of The Word.

I repeat here this vital aspect of the acoustic semiosis: it confirms these facts concerning mind and time as per the theology of semiotic forms, insofar as it readily divides into two juxtaposed means of the articulation of its signs: the simultaneous, expressed as harmonic intervals, and the successive, expressed as melodic intervals. These are fundamentally juxtaposed aspects of time itself. In a musical score, these are written according to the vertical (simultaneous) and horizontal (successive) planes of the notated page. The fourfold harmonic structure, the chord, is constituted by four harmonic intervals. These combine the major harmonic tones, I, III and V, with that of the relative minor in the root position. This minor/major seventh chord articulates the semeiacoustika representative of hybrid intentional modes, since it combines in one simultaneity, the minor which announces the distal mode and the major which announces the proximal mode, in either polarity perceptual or conceptual.

An example of this hybrid is the minor chord representing desire, and the major chord representing knowing: G-Bb-D-F in combination. In itself, the chord G-Bb-D is the chord G minor; in itself the chord Bb-D-F is Bb major. The 2-3 cadence in the minor, is identical to the 7-8 cadence in the major: both resolve in the Bb as the ascending tone. These chords can and do combine, forming the minor/major seventh chord. Hence this particular harmonic interval voices an occasion of desire-and-knowing, the simultaneous occurrence of a conative, that is, distal mode, desire, and cognitive, that is, proximal mode, knowing form of intentionality, which are together indissolubly related. This is an example of a hybrid, perceptual form of intentionality, representative of the the identity of The Holy Spirit, as are all hybrid intentional modes. Their togetherness, or unity, tells for immanence, as for Pneumatological intentionality. Both desire and knowing belong to the perceptual pole, and as such, are susceptible of hybridisation, or conjunction. The occurrence of identically related conceptual forms of intentionality is no different. Nor is that of the same two polarities in the aconscious order. These structures obtain in the same manner. In each case the minor/major seventh chord (harmonic interval(s)) are semiological articulations of the same atemporal ordering of the entities in question.

The significance of the combination of the two interdependent temporal perspectives for theology is paramount. By 'temporal' I refer here to temporality, that is, diachronic and successive, actual temporality, and atemporality - the eternal or timeless ordering articulated by concurrent ('simultaneous', synchronic) harmony. In other words, I am using the phrase 'the two interdependent temporal perspectives' to mean the integration of components of consciousness viewed both sub specie durationis and sub specie aeternitatis. It is difficult to overemphasize the theological value and import of the acoustic semiosis for the doctrine of consciousness (logos). We shall return to it in due course.

As mentioned above, the hand and the mandala are inextricably interwoven. The mandala in its simplest two-dimensional form as a reticulate of twelve contextualised components registering the six conceptual and six perceptual radicals of consciousness, both in terms of semeioptika and semeiacoustika, stems from the doctrines: Trinity, imago Dei and the incarnation of the logos. It is a visual representation of the categoreal propositions contained in the stories of creation and salvation, chiefly concerning the various relational properties which obtain between them, vis-a-vis time, by means of the acoustic semiosis. It is first augured in the Tanakh (Exodus 28.15-21), in a text attributed to the P ('Priestly') author. There it is embodied in the hoshen: